MARIA RAUTAHARJU OTHER FUTURES

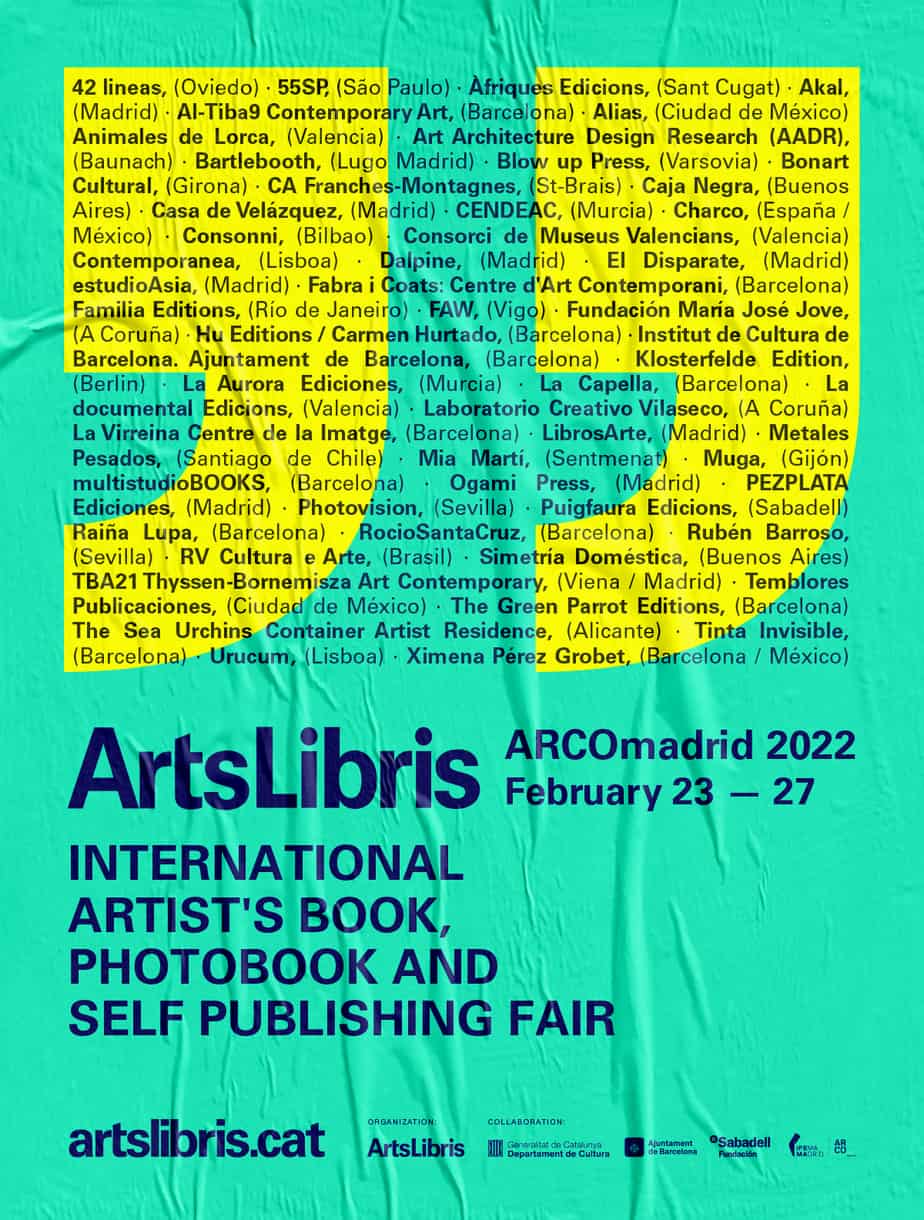

Meike Schalk,Thérèse Кristiansson, Ramia Маzé (eds.): Feminist Futures of Spatial Practice. Materialisms, Activisms, Dialogues, Pedagogies, Projections, AADR 2017, 384 p.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”, wrote Audre Lorde (1934-92), feminist poet and thinker. Lorde was referring to the feminist movement, arguing that a future distinguished by equality and justice for all is possible for everyone regardless of their class, “race” or sexual orientation when the power structures that underpin it are no longer sustained by inequality. We need a different set of tools if we are to construct new and other futures. The essays in Feminist Futures of Spatial Practice reflect the critical, searching attitude conveyed by Lorde’s words. The recent studies aid projects explored in the collection address these unequal structures through the means of intersectional feminism, taking a broad and inclusive look at the issues and placing them in the context of spatial practice and architecture. This book emerged from Introduction to Architecture and Gender, a groundbreaking course organised at the Royal Institute of Technology’s (KTH) Department of Architecture in Stockholm in 2008, which was also open to the general public to attend. It was run again in 2011 under the title Feminist Futures, this time outside the auspices of the KTH,and prompted calls for the lectures and workshops to be collated into a book. The authors comprise architects and academics as well as a wide range of experts on art, design, urban planning, gender studies and social sciences. The book has a scholarly flavour, examining issues from a primarily western perspective, but what all the contributions share isan unstinting commitment to pursuing an experimental approach. Feminist Futures of Spatial Practice takes its place alongside seminal feminist architectural titles Gender Space Architecture (1999) and Altering Practices: Politics aid Poetics of Space (2007). The politics of listening, new narratives on ageing, urban queer carnivals, care as a form of urban participation, female strategies of resistance, urban farming, fictional communities, norm-critical walking tours —when it comes to spatial practices and attitudes, the book’s approach is as inclusive as it is broad. The articles seek to further our understanding of how the “other ways”, the alternative perspectives that are key to a feminist understanding of the world, come to be marginalised or even pushed away from view entirely. The book is divided into five distinct themes, each proposing an area within architectural practice that particularly lends itself to the act of “making visible” and to the act of discovering new alternatives. In “Materialisms”, the texts explore the role our material realities play in making and shaping meaning, while “Activisms” highlights the strategies that underpin the resistance already taking place within the public realm. As the title readily suggests, the texts in “Dialogues” tune an acute and sensitive ear towards the different types of possible human dialogues, looking at conversation both as a tool and as a working method. “Pedagogies” is an investigation into the relationship between different knowledge perspectives aid progresses made. “Projections” takes a critical look at narrative strategies and our definitions of history and heritage and their role in constructing new possible futures. What means do we employ to project knowledge, and indeed what sort of knowledge we project in the first place, in our quest to produce yet further knowledge? Feminist thinking is not yet 93 inherent to the discipline of architecture. It remains an external factor, relying on other artistic and scientific disciplines and social movements for its momentum here. In “Architectural Flirtations, Formerly Known as Critique”,teacher and researcher Brady Burroughs proposes a fascinating way for approaching the existing structures of architectural pedagogy, suggesting what she terms architectural flirtations as a way of discovering new and “other ways of doing things”. The act of flirtation can be usefully employed to recognise and reveal the well-established and rather earnest understanding of what constitutes architecture and then used to engage it in playful experimentation. In this sense, the act of flirtation is a means of engagement and openness; boundaries become blurred and both sides gain a new capacity for change. True to the title of the books, Burroughs also touches on the conceptual difference between architecture and the broader and more multidisciplinary notion of spatial practice. Her emphatic message is that critical feminist spatial practice must refer to itself as architecture to allow the discipline, and our understanding of it, to change and evolve. The collection reflects the current notion of feminism as an attitude that can be used to deliver critiques at the doors of prevailing normative and power structures. In demonstrating the different guises a theoretical approach can assume when it is brought to life as spatial activism, our understanding of this notion is at once deepened and brought to bear on the architectural context itself. The book is by no means an introduction to feminist thought; there are no attempts at smoothing out the complexities and difficulties of the subject matter at hand and the texts demand both engagement and patience from their readership. Readers with an interest in feminist theory and philosophy will enjoy the references to wellknown and less well-known theories and thinkers. The book presents a view of the future that is a call for openness and a demand for diversity and new alternatives. Non-linearity and messiness are its virtues. In the words of the philosopher Elizabeth Grosz, “the future is that openness of becoming that enables divergences from what exists.” The strength of this book lies in the wealth of micro-strategies, radical ideas and theoretical and critical questions it presents, which allow the reader to glimpse at and desire other futures. In striving for those futures, we must also strive to re-define what constitutes architectural thinking and practice.

MARIA RAUTAHARJU (b. 1990, architect) searches for ecologically and socially sustainable ways to practice architecture.

ARK

Arkkitehti / Finnish Architectural Review is one of the oldest still running architectural publications in the world – and the only architecture-centric cultural magazine in Finland. It observes and showcases timely phenomena and topics in current Finnish and international architectural culture and discourse. The magazine presents projects in architecture, urban design as well as research, writing, exhibitions and publications. Architectural Competitions in Finland is published as a supplement to the magazine. Each issue is built around a discursive theme. All content appears in both Finnish and English and as such the magazine provides a vantage point into Finnish architecture also for the international readers. Finnish Architectural Review is the only bilingual Nordic architectural publication. The magazine is geared at everyone interested in architecture, urban design and the built environment.